By Ahmed Younis

Picture this: A group of Impact Fellows, armed with laptops and determination, diving into the murky waters of cyberbullying research. Our mission? To create a framework that could help AI systems recognize and categorize the many faces of digital cruelty affecting Gen Z and Gen Alpha.

But where do you even begin?

Precious, one of our fellows, started with what seemed like a simple Google Scholar and PubMed search. Her fingers flew across the keyboard as she typed: “cyberbullying amongst teenagers,” “cyberbullying in school,” “categories of cyberbullying,” “social media bullying,” “cyberstalking.” The results? Overwhelming. Hundreds of papers, each claiming to have found a piece of the puzzle.

“I realized quickly that not all research is created equal,” Precious reflected during one of our sessions. “Some papers were from 2010, talking about MySpace. Others focused on 30-year-olds. We needed something current, something real.”

Before we could dive deeper, we needed ground rules. Like detectives building a case, we established our criteria:

This wasn’t just busy work. It was about ensuring that whatever categories we created would stand up to scrutiny—both from researchers and from the young people whose lives we hoped to impact.

As we waded through 40+ papers, a pattern emerged. Some researchers focused on the how—the methods bullies use (screenshots, fake accounts, group exclusion). Others focused on the why—the intent behind the cruelty (humiliation, control, revenge).

The debate got heated. Should we categorize by platform? By severity? By psychological impact?

Then came the breakthrough: What if we organized by the nature of the harm itself?

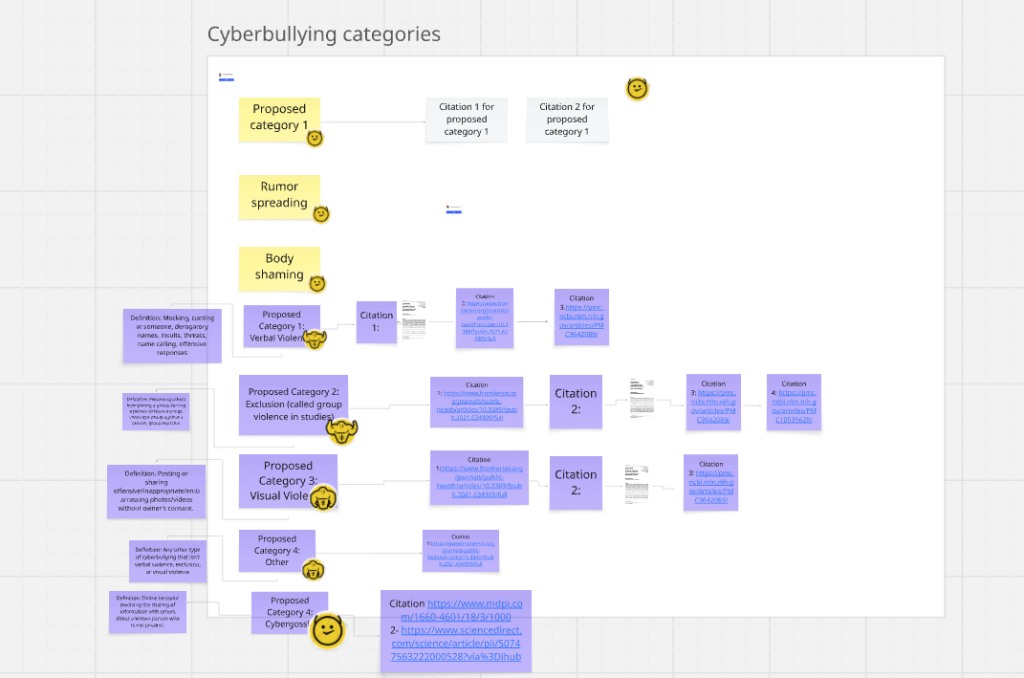

After weeks of reading, debating, and voting on our now-famous Miro board (those purple and yellow sticky notes became our battlefield), four main categories emerged from the chaos:

What we found: This was the heavyweight champion of cyberbullying research. Nearly every study we examined had something to say about verbal aggression online.

The evidence: Studies from Frontiers in Public Health (2021) and PMC (2022) painted a disturbing picture. Words aren’t just words in digital spaces—they’re permanent, shareable, and amplifiable.

Real-world translation:

Racist attacks: When hate speech hides behind screen names

What shocked us: The rise of visual platforms created entirely new forms of harm that didn’t exist a decade ago.

The evidence: Multiple studies, including comprehensive reviews in PMC (2022), showed how images create lasting digital footprints of humiliation.

The horror stories:

Meme-based bullying: When someone’s worst moment becomes everyone’s joke

The revelation: Sometimes the cruelest bullying involves no words or images at all—just deliberate, coordinated isolation.

The research: Studies from PMC (2022) and (2023) revealed how digital exclusion creates invisible wounds that traditional anti-bullying programs miss entirely.

How it happens:

The discovery: As we dug deeper, one fellow noticed something. “Wait,” they said, pointing to multiple studies, “gossip keeps coming up, but it’s different from direct harassment.”

The pattern: Research, including a longitudinal study on “Mechanisms of Moral Disengagement in the Transition from Cybergossip to Cyberaggression” (2021), showed how digital gossip operates as its own category—not quite exclusion, not quite verbal assault, but a corrosive force nonetheless.

The reality:

Why this matters: Technology evolves faster than research. New platforms create new forms of harm. This category acknowledges our limitations.

What lives here:

The voting process became a masterclass in collaborative research. Our Miro board transformed into a war room of yellow sticky notes, each representing hours of reading, thinking, and debating.

Some categories had unanimous support. Others sparked fierce debate. “Is catfishing its own category or part of impersonation?” “Where does algorithmic harassment fit?” “What about AI-generated harassment?”

In the end, we voted. Not because voting makes something true, but because it forces us to defend our positions, cite our sources, and think critically about real-world applications.

These aren’t just academic categories. They’re tools for:

Tracking evolution as new platforms create new problems

As I write this, our fellows are diving deeper into prevalence data. How common is each type? Which platforms enable which categories? How do these patterns shift across cultures and age groups?

The yellow sticky notes on our Miro board represent more than research papers—they represent real kids facing real harm in digital spaces. Every category we defined, every subcategory we detailed, connects to someone’s story of pain, resilience, or both.

We started with a simple question: How do we categorize cyberbullying?

We’re ending with a more complex understanding: These categories aren’t just labels. They’re a map for navigating the digital battlefield our youth face every day. And with this map, maybe—just maybe—we can help them find their way to safety.

The Impact Fellowship continues to research cyberbullying prevalence and intervention strategies. Our next phase involves analyzing prevalence data across platforms and populations to better understand which forms of cyberbullying affect which communities most severely.